Though we want our young people to enjoy healthy, physically active lives, it’s also important to recognise that some young people are at risk of exercising “too much”. Typically, the young people most at risk here are the young aspirational athletes who are involved in high volumes of programmed sport. Coaches, medical practitioners, and parents are increasingly recognising that overtraining and high levels of competition stress can produce negative outcomes for young athletes. As such, effective monitoring of training and competition loads in youth sport is crucial, especially for aspirational or highly motivated young athletes. Below, we outline why it’s necessary to prevent overtraining, explain the current guidelines on training volume and intensity, and advise on the best ways to monitor the training load of individual athletes at grassroots level.

In This Article

Why Monitor Young Athletes’ Training and Competition Load?

Improving Wellbeing and Preventing Injury

Performance Considerations – Understanding the Training Principle of Supercompensation

Volume Guidelines for Youth Sport Participants

Measures of Intensity: Subjective and Objective

Practical Considerations for Collecting and Analysing Data

Training Load Guidelines for Young Athletes

The Acute: Chronic Workload Ratio

Progressive Overload Principles

The Messiness of Youth Sport Environments

Key Considerations for Parents

Key Considerations for Coaches

Why Monitor Young Athletes’ Training and Competition Load?

Improving Wellbeing and Preventing Injury

Sustaining an appropriate level of physical activity is vital to building and maintaining physiological and psychological health. But excessive training and competition loads can negatively impact children’s wellbeing, cause overuse injuries, and lead to overtraining syndrome.

The bones of growing children cannot handle as much stress as those of fully-developed adults, and injuries occur more frequently in adolescence during their period of peak growth velocity. As such, young athletes need adequate recovery periods between activities that repeatedly stress their musculoskeletal system, and coaches and parents should be vigilant for the signs of overuse injury:

- The gradual onset of pain

- Aches and stiffness

- Prolonged periods of pain

- Swelling

- Point tenderness

- Pain or injury that causes a child to miss a session

- Recurring injury problems

Overtraining syndrome occurs when someone undergoes a bigger training and/or competition load than their body can recover from before their next session or competition. Constant overtraining can negatively affect the body’s hormonal, biological, and neurological systems, result in declining performance levels, and cause both injury and illness.

Signs of overtraining syndrome include:

- Reduced performance in sport and/or school

- Reduced motivation to engage in sport

- Fatigue

- Mood swings

- Rapid weight-loss

- Changes to sleep habits

- Decreased appetite

- Increased occurrence of injury, illness, or infection

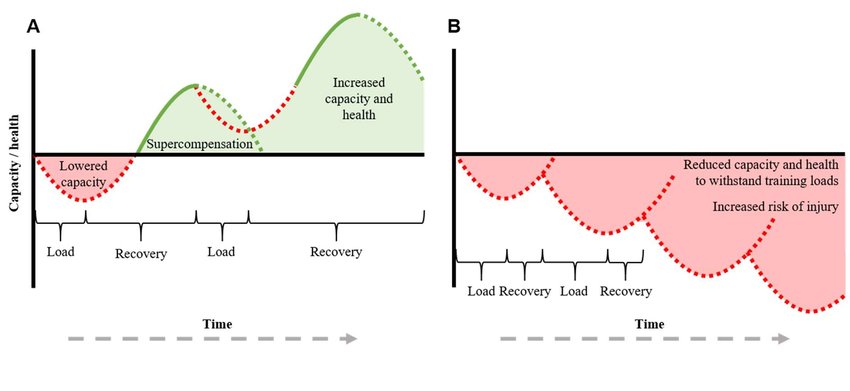

Performance Considerations – Understanding the Training Principle of Supercompensation

As mentioned, overtraining can have a negative effect on performance, while overtraining injuries can prevent athletes from participating in sport altogether. However, physical training is required to improve fitness and enhance physical capacity. Performance improvements, especially physically, will not be realised in an athlete if the level of stress is inadequate (i.e. if training is too easy or they are not training enough). However, a lack of adequate recovery time, or a training stress that is too high, can mean:

- Performance gains from improved fitness (for example, increases in aerobic and anaerobic capacity, or increased strength) are not realised due to supercompensation in the body.

- An accumulation of fatigue further impairs performance and increases injury and other health risks.

Ultimately, rest is the most essential part of training for inducing optimal biological adaptations, as outlined by the principle of supercompensation.

A successful supercompensation process takes into account:

- The overall health of an athlete, i.e. levels of inflammation, overtraining, mental stress, and fatigue etc.

- Adequate training intensity and volume.

- Adequate rest (passive or active).

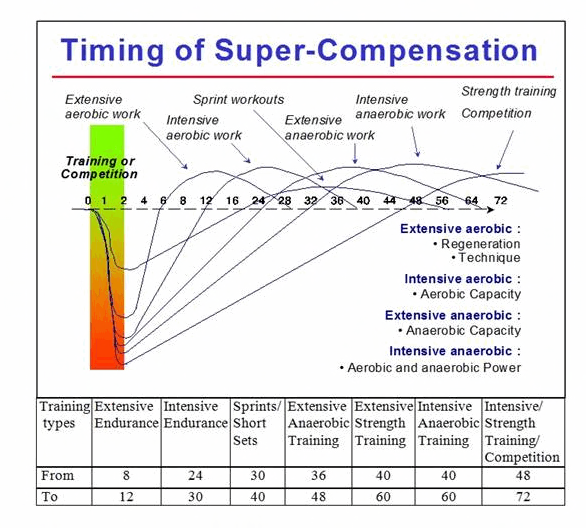

It’s important to recognise that different types of training (for example, aerobic versus strength training) will see different types of supercompensation responses, and therefore have different rest requirements.

Other factors that should to be accounted for when thinking about the appropriate rest to enable supercompensation are:

- Current/baseline level of fitness (for example, volume intensity and workload at the start of pre-season should account for baseline fitness level, and will likely need to be lower than during other parts of the season)

- Chronic workload (more on this below).

- An understanding that muscles recover much quicker than other key body tissues for exercising (such as bones and tendons).

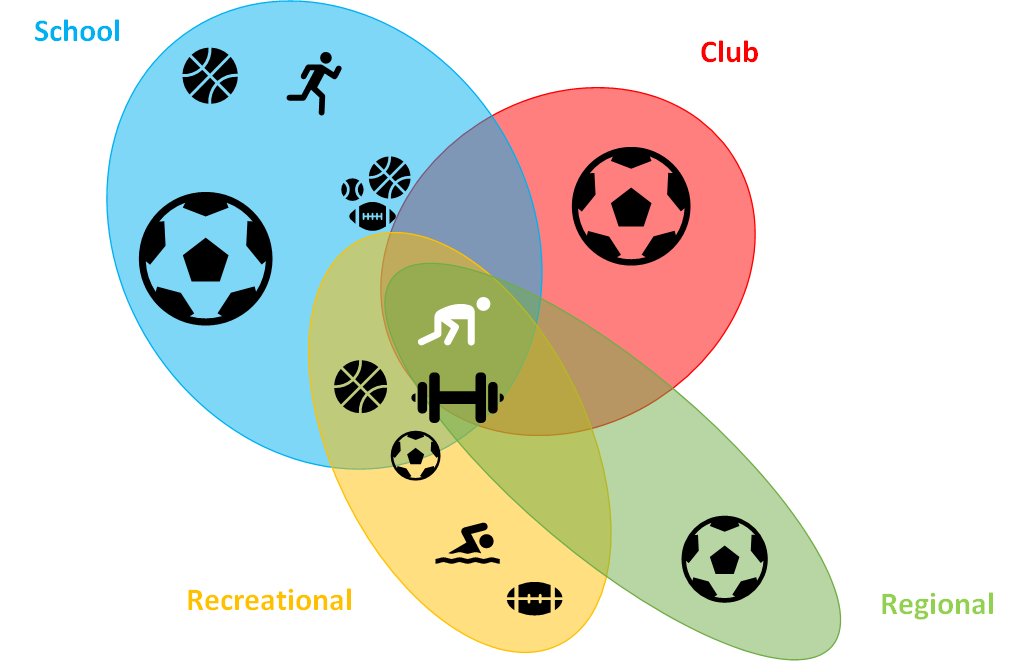

Ultimately, the tipping point between positive and negative training effects depends upon a variety of factors, including the individual and the type of exercise. This lack of homogeneity means coaches and parents must pay close attention to their athletes in order to prescribe appropriate levels of training and recovery. Further complicating this is the fact that, for many young people, the ‘total’ amount of sport they participate in is via multiple programmes, settings and stakeholders. As such, the various stakeholders, especially coaches, may not have a cumulative perspective of how much sport and other physical activity an individual young person is doing.

What is Volume?

The first step to monitoring and regulating an athlete’s physical activity is to understand what makes up their training and competition load. This can be broken down into two components: volume (the duration of time spent training and competing) and intensity (the rate of physical, mental, and emotional exertion due to training and competing). Volume is the easier of these two components to measure and monitor.

Volume Guidelines for Youth Sport Participants

The Australasian College of Sport and Exercise Physicians provides the following recommendations regarding suitable training and competition volumes for children:

- Total sport participation (both training and competing) should not exceed 16 hours per week across all sports played.

- The ratio of hours spent in organised sport (i.e. sport that is structured, goal-oriented, and usually led by adults) to hours spent in ‘free play’ should not exceed 2:1.

- The number of hours spent in organised sport each week should not exceed a child’s age in years. For example, a 9-year-old should not train or compete for more than nine hours per week. This supersedes the first recommendation if the two do not align.

- Evidence-based load guidelines for specific sports should always be adhered to.

It’s important to take an individual approach to these guidelines. Biological age differences can mean that an appropriate training load for one child is not suitable for another child in the same age group. Similarly, non-sporting activities such as schoolwork and exams can also contribute to fatigue and should be factored into considerations about training load.

It should also be noted that the recommended total hours of participation are neither a target nor a level beneath which any amount of physical activity is okay. We should view this figure as a signal; as a child’s hours of participation approach this signal, we must become more vigilant for the signs of overuse injury and overtraining.

Intensity

Coaches, parents, and sports administrators should also strive to monitor the intensity of physical activity undertaken by young people in order to understand their training and competition load. To begin, we need to recognise the two components that make up the total load (or intensity) a person experiences: external load and internal load.

Put simply, external load is the amount of “work” a person completes during a period of physical activity, while internal load is the psychological and physiological stress they experience in response to that activity. There are a variety of methods to measure external and internal load, and coaches and/or parents should track both where possible, giving themselves a fuller picture of a young person’s total training and competition load and equipping them to alter that person’s schedule if necessary.

Measures of Intensity: Subjective and Objective

The methods used to measure intensity can be either subjective or objective. Common objective measuring tools include GPS tracking devices that measure athletes’ movement and speed (external load) and monitors to track heart rate and the rate of oxygen consumption (internal load) during exercise. Most community and school organisations are unlikely to have the equipment, time, or skills to apply these types of intensity measures.

Subjective measuring tools, such as questionnaires, are often used to gauge internal load, inviting participants to record things like their rating of perceived exertion after training or competition (RPE) and their sense of wellness and wellbeing. Besides being more accessible to sports clubs without sophisticated load-monitoring equipment, some studies have even suggested that subjective markers could provide a better insight than objective measuring tools.

Practical Considerations for Collecting and Analysing Data

In addition to providing a means for grassroots clubs and schools to monitor training load without expensive devices and software, questionnaires can also involve participants in the monitoring process in a way that empowers them and gives them greater ownership of their sporting journey. But if we monitor the training and competition loads of young people, it’s essential that we use the data properly.

No matter how it’s collected, data should be analysed in a way that’s both context- and sport-specific, accounting for the needs and abilities of individual participants and the physiological demands of the sport. And the results of this analysis must underpin informed training decisions — guiding us to make adjustments to individual training programmes as and when required, in a way that promotes both the welfare and the performance of young people participating in sport.

Training Load Guidelines for Young Athletes

The Acute: Chronic Workload Ratio

The acute:chronic workload ratio calculates an athlete’s total workload by breaking it down into two parts: the acute load, usually representing the cumulative workload across a single week; and the chronic load, giving the average weekly workload across a four-week period. In this relationship, acute load represents fatigue while chronic load provides a measurement of overall fitness.

A person’s risk of injury is relatively low if their acute (weekly) training load is approximately equal to their chronic workload, though the risk increases exponentially if they experience a significant spike in their workload in a given week (represented by a ratio of 1.5 or higher). Numerous studies have found the acute:chronic workload ratio to be an effective predictor of injury, identifying an optimum ratio of between 0.8–1.3.

Progressive Overload Principles

Research on the acute:chronic workload ratio emphasises the need to be cautious when increasing the athletic workload of young people. Exposure to load enhances the body’s ability to tolerate it, and a systematic increase in training load can help young people to improve their fitness, but only if that increase doesn’t cause injury.

Studies have shown that when an someone’s workload increases by 15% or more relative to the previous week, their risk of injury also increases from roughly 10% to almost 50%. Consequently, progressive overload principles advocate the close monitoring of week-to-week changes in workload, with load increases limited to less than 10%. A person can reduce their injury risk further by alternating between low-, moderate-, and high-intensity training days.

Rest and Recovery Principles

According to the American Academy of Pediatrics Council on Sports Medicine and Fitness, children should have at least one day per week off from organised sport and play no single sport for more than five days per week. It also recommends that young people take 2-3 months per year off from their chosen sport in order to regenerate, recover from any injuries, and reduce their risk of burnout.

To further reduce the chances of burnout, parents and coaches should schedule longer breaks from training and competition every 2-3 months and encourage children to pursue a variety of different activities and sports, helping them to become well-rounded people as well as athletes.

Holistic Factors

It’s important to remember that every child is more than just the sports they play. Young people’s lives are multifaceted and complex; they have an array of different interests, demands, concerns, and commitments that compete with sport for their time, energy and enthusiasm. Things like schoolwork, exams, and other sports and extracurricular activities all place physical and psychological demands on children.

Homelife and relationships with parents, teachers, and peers can affect young people’s motivation and levels of engagement, while factors like diet and sleep quality can impact their mood, performance, and physiological regeneration. Appreciating that physiological and psychological exertion outside of sports affects the overall workload that a young person can safely tolerate, it’s vital that coaches, parents, and sports administrators pay close attention to children, observing for both emotional and physical changes; remember these external factors when a child experiences a dip in performance or capacity; adapt the training and competition loads of young people when required; and always remain supportive and empathetic.

The Messiness of Youth Sport Environments

Managing the training load of young people is often complicated by the messiness of youth sport environments. Many children play a range of different sports and are frequently faced with competing schedules, while coaches regularly have to manage multiple stakeholders, such as parents, teachers, and other coaches, besides the young athletes themselves.

For the sake of their overall development, as both athletes and people, we should encourage children to participate in a variety of different sports and non-sporting hobbies. But this creates a need for coaches and parents to coordinate in order to ensure that the extracurricular demands placed on children aren’t too high. An example of this kind of cooperation could be a child missing the occasional training session in one sport during weeks when they’re competing in another, or reducing sport load (i.e. training time) when they have school exams.

No matter how we reach these compromises, it’s imperative that the responsibility to manage competing schedules isn’t left solely to children, and that the adults around them work together to create a schedule that enables them to train, compete, fully engage in school, and explore a range of different interests without becoming overburdened. This approach, with parents, coaches, and young people working together in partnership, is key to helping those young people avoid physical and psychological burnout while enjoying well-rounded and active childhoods. Importantly, coaches that share the same athlete, should connect (or be connected by the parent) if perceived or real risks of schedule conflict and overload are identified, enabling them to coordinate and manage training and competition schedules to best support the child.

Practical Takeaways

Effectively managing the training and competition load experienced by young people is crucial to helping them stay healthy and remain engaged in sports throughout their childhood and beyond. Most of this responsibility falls to parents and coaches, especially at grassroots level. Fortunately, there are a few simple steps that they can take in order to maximise the wellbeing of young people and minimise the chances of overtraining and injury.

Key Considerations for Parents

- Ensure young people take adequate rest and recovery periods on both a short-term and a long-term basis. This means taking at least one day off from organised sports per week and a 2-3 months break from each specific sport every year.

- Monitor increases in training load and advise young people that their training load — whether that’s total distance run, training time, repetitions, or some other metric — should not increase by more than 10% each week.

- Encourage children not to feel pressure when participating in sports: remind them that the primary aims are to have fun, acquire skills, and practice good sportsmanship.

- Educate yourself in signs of overuse injury and overtraining syndrome and open a dialogue with coaches about how to monitor for them.

- Teach children to look for these signals, explain why it’s important, and encourage them to recognise signs of fatigue and adapt their training when necessary.

- Be observant for signs of reduced motivation, loss of enthusiasm, declining academic performance, and other indicators of psychological burnout.

- Share your child’s training and competition schedule with all of their coaches, giving them a fuller understanding of your child’s workload and allowing them to adjust their demands accordingly.

- Share this advice with other parents and encourage a collective approach to monitoring training and competition load.

Key Considerations for Coaches

- Learn the full lists of sporting commitments of the young people you coach (in both school and outside sports clubs, including the sport you coach as well as other sports). Understand their precise training and competition demands and liaise with their other coaches in order to take a coordinated approach to workload and monitoring.

- Establish positive relationships and open lines of communication with children’s parents and find out the additional commitments that they have away from sport. This will enable you to take a holistic approach to coaching that doesn’t overburden them physiologically or psychologically.

- Use guidelines regarding training volumes as a signal (but not a target). As the number of hours someone spends training and competing each week approaches this level, be more vigilant for signs of overuse injury and overtraining syndrome.

- Pay close attention to the training and competition loads of everyone you coach, and encourage them to do the same. Build trust with the young people you work with so that they feel comfortable informing you when they identify signs of overtraining or feel that their workload is too high.

- Remember that all young people are different. An appropriate training load for one child might not be appropriate for another, even if they are in the same age group or have similar physical or technical attributes.

- Consider what activities might support rest and regeneration in your training sessions (for example, video or tactical sessions), and what tactics or rules you would put in place if you identified that a young athlete was fatigued.

- Coaches who share young athletes with other coaches can be susceptible to trying to ‘squeeze’ as much as they can into their limited contact time with said athlete(s). This can create spikes in intensity and load. Be vigilant for this in your own coaching and be mindful not to do it.

- Don’t be afraid to be adaptable. If it appears that the training and competition load for a child is too high, change it.

Image Source: Canva