We know that coaches are pivotal to young people having great sport experiences. Great coaches create quality sport environments for young people. But what goes into making a great coach?

Importantly, as a Sport Leader or Sport Administrator, what is your role in supporting coaches to be great? Are you setting your coaches up for success? In the following guide, we discuss how Sport Leaders and Administrators can create and support their coaches, so their coaches can be their best.

The system you lead sets the ‘rules’ for how a coach can coach

People’s behaviour is constrained by the ‘rules’ around them. These ‘rules’ are often referred to as the system/s. They are constructs such as cultures, norms, policies and procedures.

So, what does this mean for sport leaders and administrators?

The ‘rules’ you oversee and influence (whether purposefully, e.g. policies; or inadvertently, e.g. culture) inform, underpin and influence how coaches will and can coach.

With this in mind, we have developed the following guide to support Sport Leaders and Administrators to think though some key ways in which they can support their coaches. Detailed below are four key considerations for sport leaders and administrators when it comes to setting ‘rules’ for the system/s, which in turn impact coaches, how they coach and ultimately, the experience of participants.

These four considerations are:

- What is your organisation’s purpose and philosophy (Do you have one? Is this captured?)? Importantly, is this well communicated to your coaches?

- Competition structures inform coach behaviours! Are there competition structures that you can alter to enable better coaching outcomes and participant outcomes?

- How does your organisation measure a successful coach?

- How do you support coaches to grow – invest in quality coach development!

What is your organisation’s purpose and philosophy (Do you have one? Is this captured?)? Importantly, is this well communicated to your coaches?

Assuming that your organisation’s purpose and philosophy is well aligned to Balance is Better, how do you then ensure coaches know and understand this purpose and philosophy? Furthermore, how do you check to ensure that their coaching behaviours (i.e. the way they coach) are aligned to purpose and philosophy as well (it’s one thing stating that you understand, it’s another to demonstrate that you understand through practice).

Birkenhead United Association Football Club developed a Club Philosophy Document to support all stakeholders involved in their club, and in particular to guide player and coach development. Tony Reading, former Director of Coach Development at Birkenhead United, and the author of the document, provided the following commentary on the driver behind creating the document,

When I first started working for the club, my role was Coach Development Manager. I began to ask myself, ‘What am I developing?’ I’m developing coaches but what am I developing them for? We want coaches that are qualified and are better at developing players but what is the actual outcome of what we are trying to achieve with these coaches? It’s got to be more than just putting them on courses and then supporting them through that and then sending them on their way. We had to be sure that if we were developing them it was in an aligned way, so there was this cohesive and collaborative approach to player development so then to do that we had to dig deeper, what is this club about? Why does this club exist? What are the values of this club? So if you coach for this club you have to understand the ‘why’ around why the club exists, the values that the club represents, what are we trying to produce at the end – it’s the best first team players that we can for the players that want to go down that path; or for the players that don’t want to go down that path and want to play to enjoy it, we want to create people that fall in love with the game and play the game for the rest of their life.

Importantly, Tony discussed how the work wasn’t finished when the document was completed. Just as important was making sure that the document got into people’s hands and that they were supported to read and make meaning of it. This could be equally applied to helping coaches to understand and make meaning of any philosophy, values, or behaviour statements that organisations might have. To support this, things that Tony and the club did included:

- Made printed copies available in their clubroom on the coffee tables.

- Included copies of the document in all coach induction packs.

- Held workshops and forums with coaches where they talked through the Club Philosophy document.

- Scheduled Facebook posts and emails to communicate parts of the document in a bit-by-bit approach.

- All coach development programmes run at the club integrated the use of the document.

You may note that the document wasn’t just communicated to coaches, but other stakeholders, especially parents. Tony discussed how in doing this they created better awareness in their wider community about the club’s philosophy and ultimately started to see stakeholder behaviours being self-policed (e.g. parents and coaches reinforced other coaches providing players equal game time).

Read more about the Balance is Better philosophy.

Key Lesson: Make sure your coaches know what your organisation’s purpose and philosophy is. Ensure that there are feedback loops so that you can check that coaching behaviour aligns with your organisation’s purpose and philosophy (e.g. observe coaches coaching; get feedback through surveys from parents and young people).

Competition structures inform coach behaviours! Are there competition structures that you can alter to enable better coaching outcomes and participant outcomes?

Sport is inherently competitive, and that is a good thing. Unfortunately, when the drive to win becomes a drive to win at all costs, issues in youth sport become more prevalent. A win at all costs approach to coaching likely means an undervaluing of the importance of:

- the long-term athletic development of athletes and young people

- the holistic development of young people

- the enjoyment of young people

The key question here is what and how can you alter competition structures to provide more and better development opportunities for young people, and importantly, minimise or mitigate some of the structures that underpin negative coaching behaviours.

Examples of altered competition structures to support better coaching outcomes include:

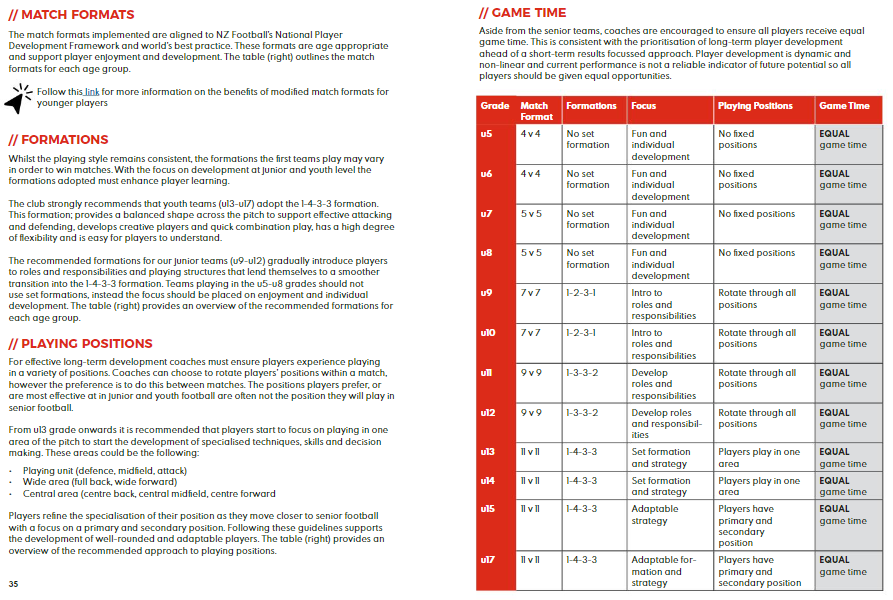

- Establishing game time policies, such as equal game time, or minimum of 50% game time policies. See example: NZ Rugby’s Half Game Rule

- Establishing position rotation policies

- Move your organisation’s emphasis and resources from either administering or entering representative competitions for a few participants to delivering skill development opportunities for more participants (e.g. skill development workshops or camps). Read about Otago Rugby’s Masterclasses.

Importantly, as a Sport Administrator or Sport Leader, consider how you get feedback into the design of competition structures, especially the interplay between competition structures and coach behaviours (Hint: talk to your coaches).

One key consideration for Sport Leaders and Administrators is how to balance the celebration of performance outcomes (especially for young people) with the celebration of other outcomes attained through sport (growth, development, fun). i.e., how do you measure success?

Key Lesson: Understand how competition structures influence coach behaviours. What structures drive negative or unhelpful behaviours in coaches, and can these structures be altered? Get input from your coaches to help understand these structures, there impact on coaches and how they could be reimagined or redesigned.

How does your organisation measure a successful coach?

The most tangible way that we measure success in sport is by performance (did we win or lose?; what was our time?). As such, by proxy, this is the most common way we measure the success of coaches (and them of themselves). But using performance as your single measurement for determining if a youth sport coach is successful, is fraught with issues and potentially unhelpful, especially for young people.

So, what are some alternative ways of measuring the success of a coach?

- Are coaches supporting young people to learn to love a sport?

- Are coaches supporting athletes with their long-term development?

- Are coaches supporting young people with the holistic development of themselves?

You would be right to think that finding or collecting evidence to quantify or qualify the measures above is a bit harder than looking up a results table. As an aside, this is a common issue in many human designed systems: that is, what matters is what we measure, but we only measure what is easy to count, so what is easy to count becomes what matters.

So, other than competition results, what other alternative forms of evidence are there?

- Smiles on faces. Genuine observation of participant body language and interaction at competitions and trainings is pretty telling. Consider planning check-ins to make sure you are gauging the environment your coaches are creating.

- Feedback from young people (and their parents). This could be collected in survey form, through conversation or by running focus groups.

- Retention. Does your organisation track the retention of its participants? You shouldn’t expect to retain 100% of people year on year, but as has been observed in some organisations, you don’t want to be on the rat wheel with 90% turn over (which means you end up putting more energy and effort into recruitment i.e. marketing your opportunities, which leaves less time and resource for other things). Look at patterns and trends of retention, especially around different coaches. Furthermore, on retention, we shouldn’t expect young people to be tied to one coach forever. Rather, this is more of a question about what the coach or your coaches are doing (or not doing) to ensure that young people grow a love of sport and stay in the game. As one colleague of mine puts it to coaches he talks to – “Don’t be their last coach!”.

A word on gathering evidence:

When you start to reflect on how you are measuring success, (i.e. what evidence are you using to determine what is good and what is poor), it can quickly become bit of an esoteric exercise. Some words of advice to keep it practical for Sport Leaders and Administrators:

- Triangulate – for each measure you are trying to prove – try collect at least three types of evidence. For example, if you are measuring whether a coach is creating a quality environment for young people you could collect evidence to understand this by:

- Observing trainings and competitions – look at participant body language. Are they engaged? Are they having fun? Be sure to write down your observations.

- Get feedback from young people via survey at the end of the season.

- Look at how many young people return to play the next season.

- Context – be sure to factor in context into your thinking and interpretation of data. Ask yourself, what contextual knowledge do you or your colleagues hold that might help to explain and interpret the evidence that you have collected?

- Acknowledge the delay in some feedback loops – sometimes, the evidence that you want to collect might not be available because there is a long delay between an input and seeing the effect. For example, coaches who want to support young people to develop leaders of character, might not see the impact of their coaching on how a young person behaves until much later.

Some key considerations for Sport Administrators and Leaders on using measures to support coaches:

- If you are involved in recruiting coaches, recruit coaches that align with your philosophy. Importantly, don’t put sport performance measures (e.g. must place top four) in contracts of coaches involved in youth sport.

- Ensure when coaches are onboarded, you outline to them how they can know they will be successful. Be transparent about how you will collect evidence to understand whether a coach is successful. This could be through conversation, in an induction meeting or workshop, or any onboarding communications.

- Collecting evidence and evaluating coaches should be framed as part of a continuous improvement approach. The purpose of evaluating a coach or your coaches shouldn’t be to stratify who is good and who is not. Rather, it’s about collecting evidence to support coaches to identify areas to develop, grow and improve as a coach.

Key Lesson: Review what information you use to determine whether a coach is successful. Do you need to reframe what successful coaching looks like to your organisation (away from results and performance measures)? If so, what evidence do you need to collect to measure this? Consider what you do with this new evidence collected to support coaches to develop. Be transparent with coaches and help them to understand how your / your organisation determines successful coaching.

How do you support coaches to grow – invest in quality coach development!

We cannot just expect anyone to show up and be a good coach straight away. Furthermore, some of the most passionate coaches coach based on outdated approaches that are not conducive to creating quality sport environments. This is where quality coach development is important.

So, how can sport leaders and administrators support quality coach development?

- Prioritise and resource the quality development of coaches. How much time and resource does your organisation put into coach development? Does your organisation have the resource to employ or support someone in a coach development role?*

- For resource limited organisations there are other organisations that may be able to provide your organisation with coach development support. See Sport New Zealand’s Sport and Recreation Directory.

- Ensure coach development programmes align with Balance is Better messaging.

*One key consideration for local Sport Leaders and Administrators employing someone into a coach development role

Does your organisation have a Director of Coaching role or something similar? If so, it’s important to ask yourself is the purpose of this role for them to be a coach or a coach developer (and understand the difference)? We’ve seen many organisations employ a Director of Coaching (or the like) with the intent to grow the quality of coaching across their club/school. This person inevitably becomes the coach of the 1st team, reserves, U15a, U13a. Understandably, their time is consumed with being a quality coach, and not a quality coach developer, and consequently the development of other coaches in the organisation becomes ineffective to non-existent.

Read more: Sport NZ’s information for partners about coach development

Key Lesson: Understand what quality coach development looks like. Invest in quality coach development (this may mean reviewing how your organisation allocates resource) as primary way to improve the experiences that your young participants receive or find support to do so.

Image Credits: Canva