Bobby Newport is a senior lecturer in sport & recreation at NorthTec | Te Pūkenga. In this Q&A, Hamish Rogers talks to Bobby about his research looking at the development backgrounds of some of New Zealand’s best hockey players; whether athletes from rural backgrounds have a development advantage; what parents need to know about “programming” versus “play”; and more.

Key takeaways from the Q&A

Do rural environments provide development advantages to young athletes (compared to urban environments)?

While there’s no globally defined agreement on the definition of what a rural background looks like for athletes, Bobby spoke to some of the benefits that subjects in his research recognised had helped them succeed in hockey and attributed to growing up rurally in New Zealand.

In summary, research participants characterised their rural childhoods in the following ways:

- Being allowed by their parents to roam far and at an earlier age (in contrast to contemporaries in urban environments). This meant there was more risky play with less adult supervision or intervention.

- There was also lots of play (mucking around) in general.

Lots of risky play and play, in general, was conducive for well-rounded and excelled physical literacy, as well as the development of important psycho-social attributes such as problem-solving and communication. Research would also point to how these types of environments fostered an autonomy-supportive upbringing (i.e. were provided with lots of opportunities for decision input and decision making). Research subjects would identify how these experiences in turn had benefited their development as athletes and supported their success in sport.

Athletes in Bobby’s research also spoke about the importance of both parents and coaches.

The athletes interviewed discussed how their own parents’ support had been critical for their development and success as athletes. Support took shape in many forms, such as, introducing them to a sport, financial, travel, being there for them during challenges, etc. Importantly, the athletes interviewed recognised parents were able to give lots of time to their sport. Some participants felt that this was a benefit of a rural upbringing, where their parents were farmers with flexible work hours and/or one parent did not work or work full time.

The athletes also discussed how their youth coaches were pivotal in their journey as an athlete. Firstly, all the athletes interviewed reflected on the fact that their early sports experiences were framed with lots of positive experiences, and as such this resulted in a growing love for sport, and particularly hockey. Importantly though, athletes recognised that their enjoyment of sport at an early age was a by-product of having positive coaching.

Is there a lesson here for urban parents?

In general, positive parenting regardless of whether you are in a rural or urban environment starts with the notion of “support”. As outlined above, parent support can take shape in many forms, and this support will likely change over time in line with the different ages and stages of young athletes. Parents who continue to reflect regularly on how their parenting is responsive to their children’s needs will be well placed to provide effective and positive support that meets the changing needs of their children over time.

One key thing that Bobby spoke to that urban parents could learn from his research is the importance of connecting with their community and neighbours. In rural communities, the high level of connection between neighbouring adults helped to weave the safety net that allowed children to roam (more) safely. While not wanting to overgeneralise, Bobby wondered whether a decreasing connection between neighbours in urban communities, compared to years gone by, meant some urban parents were more hesitant about allowing their children to roam. Ultimately, better connections between neighbours might be thought of as a way to improve the conditions for children to safely roam.

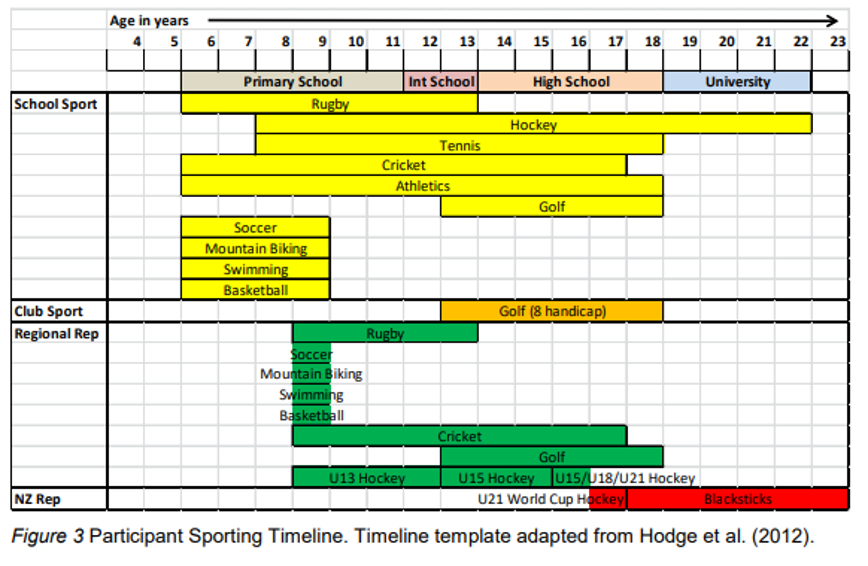

Athlete Journey Maps

Bobby used Athlete Journey Maps to illustrate the ‘collective’ sports experiences that the Black Stick’s Hockey Players he interviewed had had throughout their life.

He found that the hockey players he interviewed typically had had a diverse range of sports engagements.

These findings aligned with much of the literature around early-childhood sampling of multiple sports being beneficial to athlete development.

As one of the participants in Bobby’s research put it:

I think it’s so good that I was able to play so many different sports. I came in fresh loving it, and I wasn’t just drilled. I just got to play lots of different sports, have fun. Obviously, I was competitive, but I got to find out what my favourite sport was by default, by experimenting other with other sports. I didn’t just get chucked into one and get told to train every day for that one sport.

Parents

Bobby and Hamish, both recognised that for parents supporting aspirational young athletes, the question of how parents best support their child to find balance is complex.

For many young athletes and their families, the accumulation of sports training and competition in their lives is similar to the frog in boiling water analogy. Where the successive and increasing amount of training and competition grows slowly over time. As a result, sometimes it’s hard for parents to recognise where their child has reached a point where they might be doing too much (particularly of a single type of activity).

Conversely, it’s also challenging for parents of young people who are super aspirational and want to commit to one sport at an early age. While research shows that athletes typically benefit from a childhood underpinned by playing a diverse range of sports, at an individual level, parents will need to figure out how they best respond to and support the development needs of their child.

Coaches

Bobby also wanted to stress that many of these hockey players recognised they had benefitted in a variety of ways from positive experiences with coaches, from “the little things they said to them right through to the more, we’re gonna make this happen for you – that coach had a real massive impact.”

What’s the key takeaway here for coaches? It’s a useful frame of reference for coaches, particularly youth coaches, to think about how they are contributing to their athletes’ journeys, knowing that there will likely be successive coaches to come after them. As a coach, you a likely just one ‘link’ in a ‘chain’ of coaches that collectively support an athlete’s journey. The question coaches should ask, is how do I make sure that the ‘link’ I help form continues to benefit and support my athlete beyond our time together?

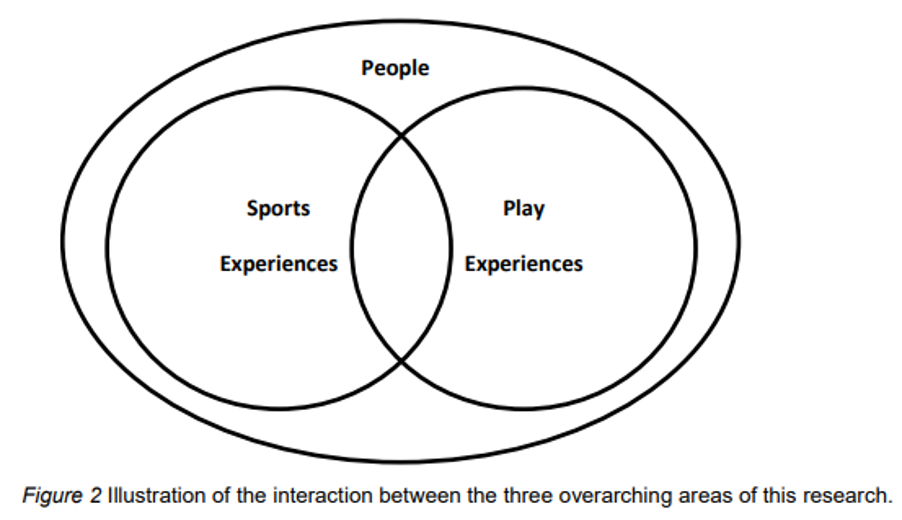

Sport and Play

While the subjects’ formative sport experiences were important, so too were their play experiences. Bobby thinks at times it’s hard to separate out these two types of experiences, as sport and sport-like activities often form the basis for play, and play often happens in sport and sport contexts.

With regards to play though, many participants in Bobby’s research commented how a playful childhood (or mucking around) was one of the key factors that they felt underpinned their development and later success as hockey players. At times, play looked like informal or backyard sport, other times it was games or role-playing. Importantly, play in rural environments typically took place outdoors.

Programming versus play

Hamish wondered whether, some young athletes, particularly in urban settings, were being subjected to ‘over-programming’. That is when children are ‘put into’ lots of adult-led activities and extracurriculars.

There were a multitude of reasons for why this might be including:

- Intensification in urban areas resulted in decreased space and environments that were conducive to young people mucking around (such as backyards).

- A relationship between both parents working and programming extracurriculars to ‘fill the gap’ between school finishing and parents finishing work.

When young people do all their physical activity through programmed activities and events, there is a potential opportunity cost where they may lose out on the benefits from play and mucking around.

From a skill acquisition perspective, lots of play opportunities allow athletes to grow their own fountain of knowledge more so than the sum of what a coach/es will be able to teach. That is, as a coach there is no way you are going to be able to support all the movement problems your athlete might have to face one day in your (or another sport). This is where play is so advantageous. Just by being exposed to more play opportunities, athletes implicitly grow their movement capability.

Photo by Markus Spiske on Unsplash