Knowing our athletes — and what they need and want — is the key to being a good coach. What benefits one group of individuals might not work for another, so it’s vital that we understand our environment and recognise how to design session plans that are suited to the people in front of us. Below, we examine the key parameters when planning a session, discuss how they can inform our practice design, and provide some practical examples of activities to deliver with U7-U12 players.

A Common Coaching Scenario

To begin, we’ll consider a hypothetical coaching scenario that is common in many grassroots sports environments:

- Our team trains once or twice per week, for two-to-three hours in total.

- We also play competitive games every weekend during the winter season.

- Many of the kids in our team play other sports throughout the year.

- Participants are aged between seven- and 12-years-old.

- We have a limited supply of equipment (such as balls and goals).

Over the course of this article, we’ll discuss ways to work effectively within the constraints of our coaching environment, and how we can utilise the Practice Spectrum to facilitate great sporting experiences for young athletes.

Understanding the Parameters of Our Practice

When designing a session, we must first recognise the parameters within which we’re working. Factors like our total number of contact hours (both per week, and over the course of an entire season), whether we play competitive games to consolidate our learning, the equipment and facilities at our disposal, and, of course, the individuals we’re working with, should all be central to our planning process.

For example, if our contact time is limited to just several hours per week, it’s crucial that our sessions flow and maximise the time that kids are actively participating (rather than queuing or listening to instructions). If our participants have been at school all day, we should create practices that enable them to move and expend energy. Lastly, our limited equipment will likely be depleted further over the course of the season, so it’s vital that our practice activities maximise participation even if resources are scarce.

In the scenario outlined above, we would recommend making practice resemble the game as often as possible. Game-based activities provide real information, enabling athletes to practise processing that information and making decisions; help us to consolidate areas of learning on gameday; and emphasise the joy and spirit of play that should exist within all youth sport environments.

To improve our understanding of what constitutes game-based activities (as opposed to isolated practices), it helps to consider our sessions within the context of the Practice Spectrum.

Utilising the Practice Spectrum

The Practice Spectrum ranges from isolated, unopposed activities (for example, dribbling a football between two cones), to a full version of the sport (such as an 11v11 match, on a full-sized pitch). Generally speaking, activities further up the spectrum (towards the ‘full game’ end) provide more realism and opportunities for decision-making, but sacrifice opportunities for repetition — and vice versa. All of our practice activities sit somewhere on this spectrum.

It’s important to note that both isolated and fully-opposed practices (in addition to the many others in-between) have value for our athletes. Our job is simply to identify which activities provide the most benefit within the context of our training sessions. It’s equally important to recognise that we can move up and down this spectrum during our sessions, or even within the same activity; for example, we might start with an isolated practice to help our athletes understand a new idea before making the activity semi- and then fully-opposed.

But, before we explore this progression through the Practice Spectrum further, we must remember the main purpose of our training session.

Appreciating the Purpose of Training

As coaches, it’s imperative that we get to know our athletes as people, understand what they need and want from their sporting environments, and let this knowledge inform our decisions. In our scenario here (working with athletes aged between seven- and 12-years-old, who also play other sports), our primary aim should be to facilitate enjoyable experiences that make them want to return each week.

Ultimately, at this stage of their development, we want kids to fall in love with sport, hopefully laying the foundations for a lifetime of participation. Young athletes with bigger ambitions can still undertake isolated practices away from training, but we must first engage them. And, in addition to producing positive developmental outcomes, activities further up the Practice Spectrum can be great ways to make sessions more fun.

Activities Across the Practice Spectrum: Two Practical Examples

Within the age groups discussed here, kids often play smaller formats and modified versions of their sports. With this in mind, we will consider two practice activities that can be adapted to a range of different sports while still encompassing the principles covered above.

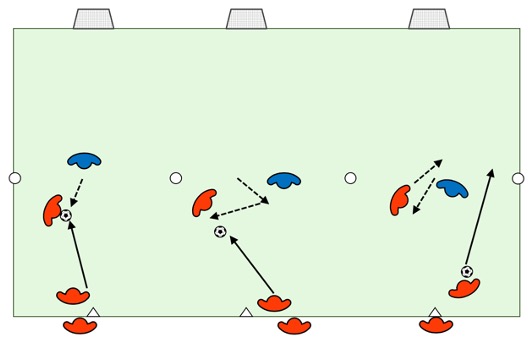

1v1 or 2v1

In this activity, we have a player receiving the ball with their back to goal. Their aim is to face forward, carry the ball past an opposing defender, and then score. We can move further up the Practice Spectrum by adding an attacker, so that the defender is overloaded. It is well-suited to sports such as football, hockey, and basketball.

Benefits

- Realism: this is a moment that sits within the larger game.

- Repetition: by setting up multiple stations at once, we can give athletes many opportunities to practise this action.

- Variety: we can ensure variety within the repetition by changing factors like the opposing defender or the attacker’s starting position.

- Relevance: this activity is suited to the age of our players, as it guarantees lots of direct interaction with the ball.

- Consequence: if the attacker does not succeed, the defender will win the ball. We can add to the sense of consequence by giving the defender a goal to score in at the opposite end of the playing area.

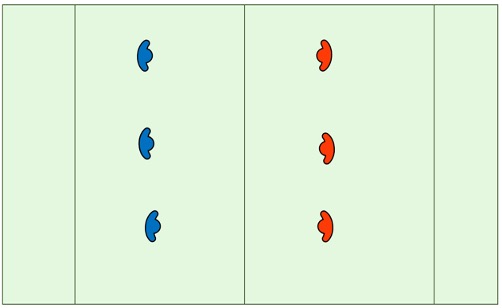

3v3 or Small-Sided Game

This expansion of the previous activity can be applied to most invasion games; small teams (starting with 3v3 games and working up as appropriate) attempt to score against each other in a small playing area. It sacrifices repetition (more athletes participating at once will generally mean fewer reps per athlete) while enhancing realism and providing scope for positional play and the development of relationships between teammates.

Benefits

- Realism: the activity is fully-opposed, meaning greater potential for decision-making.

- Variety: while there is still some repetition, these moments will be far more varied.

- Relevance: plentiful contact time with the ball to maintain player engagement.

- Consequence: goals at either end (and keeping score) give the activity consequence.

- Opportunity to practise team play: allows for individual development within a team context.

In Summary

- The parameters of our practice — such as our number of contact hours, available facilities, and the age of our players — should underpin our session design.

- When working with younger athletes, our sessions should maximise the time that they spend actively participating.

- All practice activities sit on a Practice Spectrum ranging from isolated activities to full versions of the sport.

- Opposed or game-based activities often give athletes the most benefit from our sessions.

- As coaches, our primary aim is to make training enjoyable and help kids to fall in love with sport.

Image Source: matimix from Canva Pro