We often hear that mistakes are necessary for learning. But what does that mean for how coaches respond to repeated mistakes in decision-making?

In this Q&A, Hamish Rogers sits down with Dr. Vince Minjares, to discuss his Ph.D study on shot selection in high school boys’ basketball. Vince encourages coaches to avoid simplified explanations for repeated mistakes, like ‘selfishness’ or ‘lack of ability’. Instead, Vince uses data from his study to show how such mistakes are complex, better understood as conflicts along a learning journey and shaped by factors that can be outside an athlete’s awareness or direct control. Vince shares practical tips and insights for coaches working with such athletes.

Key takeaways

- Coaches will benefit themselves and their athletes if they re-frame repeated mistakes as conflicts along a learning journey. This does three things:

- It encourages coaches to not see all mistakes equally. Whereas some are easily correctable, others require a deeper understanding of the player and their world. This is especially true of problematic yet repeated patterns of decision-making that aren’t resolved quickly or through a coaches’ standard methods.

- It positions coaches to ‘seek first to understand’. That is, coaches should think about responding to repeated mistakes by first unpacking where the conflict comes from (i.e., unpack the learning conflict).

- It shares the responsibility of mistakes resolution between the coach and player (or teacher and learner).

- Coaches should refrain from quick judgements and creating quick labels about an athlete (e.g., “they have low Basketball-IQ”).

- These labels create narratives which coaches hold about athletes, that in turn become coaching biases.

- Unpacking a learning conflict starts by learning what is going on in a players’ world, including their other teams/coaches, support system and prior history. Some questions to consider:

- How new and unfamiliar are the concepts and techniques that you are teaching or coaching to your athlete? How are athletes internally reacting to this new content?

- What is the athlete’s learning history compared to other people you are coaching at the same time? Who have they been coached by and how have they been previously taught?

- Are they being coached by anyone else? Being provided coaching advise by anyone else (e.g. a trainer or a parent)? How might that be creating conflict for the player?

- Learning about your athletes comes easier when you build trust and rapport with them. Tactics coaches may want to consider to build better rapport with their athletes includes:

- Athletes don’t care what you know, unless they know that you care.

- Make it a point to connect individually, in a non-sport specific way with each athlete at each team encounter – make it positive and warm, even if it is short.

- Use travel, road trips, off court meals, etc. as opportunities to chat to them and go deeper about their history, family and life away from the court. Use down time between games for 1 on 1s to check in on role, mood and player confidence. These are all great openings to figure out what might be happening internally!

- Reviewing film is an underappreciated way of helping athletes become more aware of patterns in their decision-making. If done in an intentional and psychologically safe way, this process can lead to dramatic changes in learning and decision-making. A few tips:

- Create team opportunities for film where players can watch, reflect and identify issues independently from what you’ve seen. 2-3 mins of unedited game flow is great for helping players self-identify patterns.

- Conversation is learning. Organise players into groups, pose an open-ended question and get them talking. After a few mins, ask groups to share what they found. Make these conversations non-judgmental. Embrace different responses, no matter how right or wrong (this fosters trust and vulnerability). Avoid the temptation to provide solutions before genuine discussion.

- In terms of content, emphasise habits that you might see but an athletes would not be aware of. Athletes don’t have your perspective and cannot see themselves during play. If doable, use group film to identify a common habit throughout the team that multiple players exhibit. If a habit is unique to a single player, individual film sessions are better contexts.

Transcript

Please note, the following transcript has been lightly edited for clarity and brevity.

HR: Hi everyone, and welcome to this Balance is Better Q&A. My name is Hamish Rogers. I am a Sport Development Consultant with Sport New Zealand and lead of the Balance is Better Website. Today, on our Q&A we’re joined by Vince Minjares. Vince is currently the Development Officer at Harbour Basketball. In addition, Vince is a Regional Coach Developer, and a National Sport Trainer for Sport New Zealand.

Vince recently earned his PhD in coaching and pedagogy. Vince – I’ll get you to talk a little bit more about that in a moment. Vince, hails from the States. Vince has had a focus, prior to his time in New Zealand, with high performance, basketball and football athletes in both men’s and women’s varsity programmes.

Vince, the scope of today’s Q&A is going to be leaning into your research, with a specific interest, around athlete decision-making. Pretty much, unpacking the common questions we hear from coaches around, “well, why do my athletes keep making the same mistakes?”. By the way Vince, congrats on completing the PhD. I know we’ve had many conversations about that, so well done. Should we be calling you coach doc now?

VM: You know, there’s some truth to the doctor, but I’d like just being called Vince. That’s fine. Thanks for the opportunity though. Really excited.

HR: Awesome. Thanks Vince. To frame our discussion today, I know you had a really good story, but we might kick onto that story in a second. Maybe before we do that, do you want to just talk a little bit about your background.

VM: Thanks Hamish for having me on, we go back quite a way. So, this is a really cool opportunity for me to, to not only talk about my PhD and, and share some tips with coaches, but also to do it with you.

Yeah look, I came to New Zealand in 2014, wanting to pursue a PhD in coaching and pedagogy, which is really, you know, the practice of teaching, and learning in sports. My background is very much in player development, and the ways in which we can do that, to sort of acknowledge the human side of things. I think the Balance is Better messaging and the programming itself really speaks to my interest in doing sport and doing coaching in a way that honours the people that we’re working with.

I think that will come out quite a bit today as we talk about kind of a quite common coaching problem, which is, responding to player mistakes, which I think is an area right for conflict and tension. And we do need to kind of wrap our head around. I’m excited to chat about that and, and broadly about the field of coaching and how it is really about people, right. And I think a lot of people can resonate with.

HR: Well, let’s dive in. When we were kind of broadly having a chat about this before we jumped online, you mentioned let’s frame this with a good story. I know you’ve got one. So, I will hand it over to you to share.

VM: I guess just as the premise, you know, there’s a recognition that in coaching, a lot of the process of coaching is very much, about, you know, player development, collective learning, improvement of team. And there’s lots of different ways to do that. And I suppose one of the key practical questions that coach has always have is, “when players make mistakes, how do I respond?”

What I’m going to do now is just walk you through, a little sort of vignette, a little case study from some research that I did a few years ago as part of my doctoral research, where I spent a year with a high school basketball team. And the goal of that project was really to dive into the learning experience itself and to try to get caught up in the weeds. I think of how messy that process is, and help coaches really get an appreciation for what they do have control over and what they don’t.

To kind of walk you through, this particular case study, we’ve got a student, we’re going to call him Nathan. Without giving you anything about Nathan, we just want you to watch this, these two possessions of basketball offense. Now this is a high school boys basketball team, and what we want to do is watch the boy in the yellow shirt and just try to get a sense for how he’s playing and what the potential conflict is. So, we’ll just play this and see what you notice.

Alright, Hamish. Now I know you’re a footballer and, but you’ve watched a little bit of basketball there. When you watch these two sequences and you can follow along with the boy in the yellow shirt, what’s your first impression about what’s happening here and, and what the issue might be?

HR: The thing that stuck out to me was you can hear, whether it was the coaches or collectively the team, there was more than one person, shouting to him, in that second phase of play, “move it, move it”. So, to me, the issue at hand is probably around speed or quickness of moving the ball. I’ll let you talk to that, but I can see how that pins down into athlete decision-making.

VM: Yeah. So, we’re talking here about mistakes and decision-making obviously, and we’re talking about a mistake and mistake actually might be a harsh word, right? You know, it wasn’t a turnover. He didn’t lose the ball, but there was a moment there, particularly in the second clip where he caught it and he held it and he paused and he really, I think we called it, he hesitated. And that hesitation, from a coaching perspective, that hesitation, there’s an issue there. You heard it from the team, you heard it from the players, sort of saying, “Hey, move it, move it, move it”. So, they want him to do something different from what he currently is. Now, again, you might not call that a mistake, but we, for the sake of it, let’s call it a conflict. A conflict in decision-making or issue in decision-making.

Well, I think what’s interesting about, you know, as a coach and the coaches that are watching, might be thinking immediately about what they might do in that situation. But when you talked to this particular player, Nathan, about the situation, here’s what he had to say.

He said, “I don’t want to take the first shot because it may be on the first pass. And if I miss, I might look bad. But with this style of training, the first shot always looks like the worst shot. I want to make sure I deserve my place. I just want to be better for the team.”

So, at initial kind of investigation, you see that there is something going on in terms of how he’s perceiving the situation of the team, not just perceiving the game, he’s got some concerns about his connection to the team, how he will be perceived by his teammates, and also sort of a misunderstanding of the way in which the team is playing, and some confusion about the style.

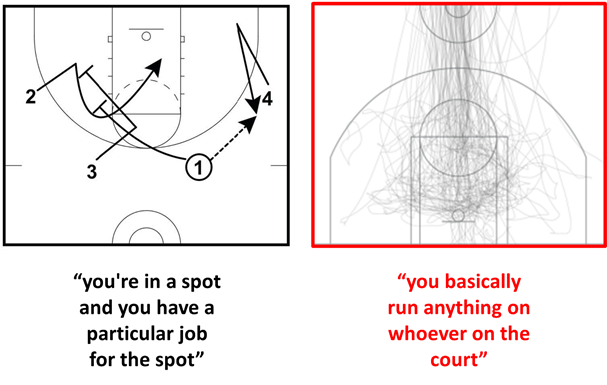

So, when we probe a little bit deeper, what he sort of brings out is this idea that the motion offense or the offense that’s playing is something new to him. He says the flow motion is something that I’ve never done. It’s not like you have a play where you go to a particular spot or have a job for the spot. You kind of go wherever you are on the court. And I’m just getting a little confused. I don’t know how to score, and I think in this comment in particular, you have probably the essence of the conflict, which I’ve kind of drawn up here as on the one hand, probably comfort in a more structured setting where he’s been given a specific job for a particular spot and he does that thing as characterized by the neat clean lines on the left side. And on the right side, you’ve got this more open what he perceived to be this very open freelance style, where you can kind of do whatever. And this is the essence of what, of where the mistake comes from, which is his construction or his perception of what is being asked of him.

And obviously, that’s a much deeper issue, beyond simply, what many coaches might have resorted to initially, which could have been something like a lack of confidence or, I hear this all the time, you know, a low basketball-IQ, things of that nature. I think. And this is the heart of what we want to get at too, which is, where is this conflict in play coming from?

Does that make sense?

HR: Yeah, it makes me think about some of the times that I’ve coached players in the past, and probably, I’ll say I’ve been guilty of not unpacking the conflict.

VM: Right? I think unpacking is a really good word. Because, you know, I’d like to share a little bit more about not just the conflict in his understanding of the situation, but also the context and the word context is a word we use often in research. But in a practical sense, in a coaching sense, it means, you know, where are we? When are we, what, where, where do we fit in the lifespan of the team and the player? That matters, you know, and I think when you start kind of unpacking this, you learn a couple of things.

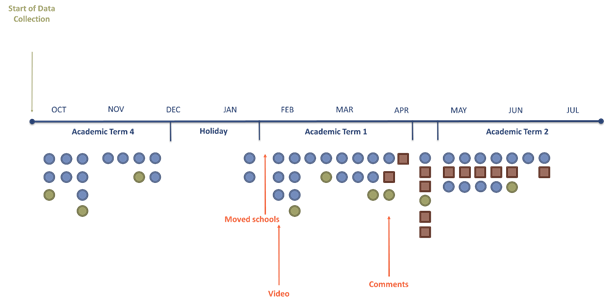

One is, this particular training, you’ll see from this little graphic, that video came from early in term one, and he was a player who’s just moved schools and, and that’s part of his story. He’s just moved schools. He’s come into a new training environment where there’s new people. There are new players. Of course, he’s going to be unsure. Of course, he’s going to be hesitant because he doesn’t know. And he hasn’t built the connections with people.

What also is impacting, is that he’s playing with a group of players who had spent all of term four going through a process. And that term four process was trainings and film.

So, they have already entered the term predisposed to what the coaches are trying to do. Ironically, he didn’t actually make his comments about how he was feeling about it until nearly the end of the term and in this graphic, the squares represent games, the green circles represent film sessions, and the blue circles represent training sessions.

And so, you can see that there’s a time span to the learning process. Where are you in the journey? Both as an individual and with respect to the team. I think that this particular situation had some issues around this player playing in a new style of training.

This was more of a game focus where there was no set plan. It was more read the situation. That was new to him. And you know, we did lots of things like two on twos with dribble rules and things of that nature, where the players were free to make decisions. I think most importantly, though, more than anything, I think this conflict for this player, for Nathan is a conflict of the structure of basketball.

“…[T]he [flow] motion we run is something I’ve never done…it’s not like you have a play where you’re in a spot and you have a particular job for the spot…you basically run anything on whoever on the court and that’s where I’m just getting a little confused. Like, I don’t know how to score.”

Nathan

Players trying to get a sense for, you know, how basketball is meant to be played or how the sport is meant to be played. And it can be something you have to tease out. It certainly requires a relationship. This research was a lot about diving into the players, perceptions and experiences of learning to play a new form of basketball. And that was a “motion offense”, which is very different from a set, structured play type of basketball.

You’ll see in this quote, we’ve got players talking to us to read and make reads and yes, there isn’t a structured, sequence or prescription. There’s a freedom, but with that, freedom comes potentially some anxiety or some uncertainty, if you’re not sure what to do. What we are seeing with this player, where some of the other place had probably already crossed the threshold of being able to kind of understand it that was the way they want it to play, and this is an example of how we were actually structuring it, in terms of some of the rules that we had for play. You know, there was some stuff around training design, but I think that, by and large, when we put them into this training environment I think Nathan in particular struggled a little bit with the conversational element of it. We were asking their opinions, you know, we were asking them to make decisions and talk through what they were experiencing. That was all new and different.

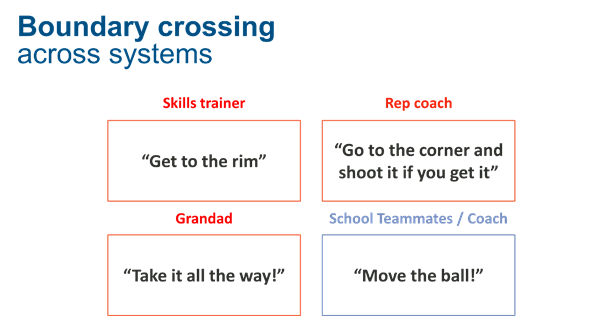

But I think that more than anything, the thing that I want to kind of speak to is, when you start breaking down where conflicts come from, and where mistakes come from. Part of what we learned very quickly is that players have been coached in many different ways, sometimes all at the same time. So, when this instance, we had a player who was being coached in multiple environments. There was contradictory information. You had a skills trainer saying, “get to the rim”. You had a granddad saying, “take it all the way”. And the parents are coaches too. You had a rep coach who was telling him, “Run this scheme and go to the corner and fill the corners and shoot it if you’re open”.

And then you have this particular environment of the school, where he was being asked to, read the game and decide what’s best based on what you see. No one is wrong here. Really what we’re trying to highlight is that sometimes these mistakes that players make are really just the natural product of being in multiple environments at the same time and trying to make sense of all of that. You know, players play off habits. They’ve got lots of kind of instinctual responses that they do that they built up over time. And when you come into a new environment, it can be hard to just simply stop doing those things. And I think a lot of coaches, because we don’t really think about where they’ve been or what else they’re doing, we’re really just focused on our team. We can run into problems by assuming that a mistake is consciously done that they’re just not following what the coaches did. They’re selfish or they’re, not interested in learning what the coach is trying to do when often that’s not the case, particularly when you unpack their journey.

So I know that sort of a long piece there, but hopefully you can see that, that in this instance, we have a story where the mistakes or the conflicts in decision-making are, are actually, they make sense when you really dive into it and try to understand what’s going on in the players’ lives.

HR: Really fascinating Vince. A couple of questions that come to mind for me is for the coach themselves in order to go through this process of reflection and unpacking, what does that look like? What’s the entry point for a coach to be able to start? Let’s say they’ve flagged an athlete as making continuously making the same mistakes. How do they start peeling that back? What are the practical applications for a coach?

VM: Well, a couple of things. Obviously the first starting point is to say that, as a coach, recognizing that mistakes happen, right? It starts with your assumptions. Not even the work of working with the players, but it starts with your assumptions. You know, mistakes happen. It’s part of the game, particularly invasion games. They’re messy. Players make mistakes. They make errors. Sometimes they’re in their control. A lot of times they may not be. So, what is your position towards mistakes?

Number two. If you want to engage in a process like this as a coach, where you learn the stories of your players, which I would recommend everyone does anyway, because you know, that creates a more intimate connection between players and coaches. Well, you need a relationship and that relationship begins the second that team is formed. You know, having rapport, talking to players, talking to everyone, not just as basketball players, but as people, having chats with them, you know, away from the team or on the side-lines. those are the two sort of first points.

And then when a conflict happens, you’re ready to jump in. And you’re ready to jump in, to try to understand first. And I think there’s a classic sort of Stephen Covey, you know, ‘seek first to understand then to be understood’, but that really applies here. I think that coaches can do a lot more to try to understand the worlds of their players.

Where else are they playing? What else are they doing? What are the other messages they’re receiving, before I jump in and say, “do this my way”. And I think there’s an important nuance there that is really important because when you’re a coach, who’s trying to develop players, you understand that that process is not straightforward. They’re going to interpret things differently, they’re going to try it, they might struggle. There’s so much that could happen. And I think coach has definitely to be patient while at the same time saying, “Hey, we’re trying to do this, I’m going to work with you to help you figure out how to do this, but I know you might be dealing with some things”.

And think about it, how many kids would willingly volunteer some of this stuff to a coach, conflicts, the misperceptions, the things that they’re struggling with, they’re going to just internalise them unless you ask them. And I think it’s incumbent upon coaches if they’re really invested in the learning process, to figure out what makes these kids tick and what’s going on. And the silence is not consent, you know, just because kids are silent, doesn’t mean that they are happy or they fully believe what’s going on. I think a lot of coaches mistake that. And I think that making the time to have those conversations with players and really learn what’s going on. In particular, learning how else are you being coached? How else have you been coached? How are you dealing with that? Because everyone is dealing with that in one form or fashion, given that we want so many kids to play sports.

HR: It is certainly fascinating. It mirrors, a lot of conversations I’m having around the sector at the moment, around, are coaches even inquiring about who else is coaching their athletes? And not just, as you said, not just coaching. There’s a myriad of other different stakeholders now who are inputting, into the experiences that these young people are having, right.

Are there any key practical takeaways? We have coaches who live and breathe in a pretty busy world. Where do they start and how do they make steps into this space where they’re not just getting to know their players better, but their contexts, their histories, their stories, and then weaving it in to their own decision-making about how do I support this young person to develop?

VM: I would encourage coaches to stop turning immediately to the sort of quick judgment. Just stop it. You know, “he’s selfish”, “he’s lazy”, “She doesn’t know how to play”, “she doesn’t want to learn”, “she’s got a bad attitude”. All of these quick labels are harmful. They’re harmful because what they do is they create narratives about players and then coaches, once they have these narratives around players, they turn blinders off.

They don’t want to pass those labels. It’s easy. It’s easy to go to the players who are not making mistakes or who you already understand and connect with. It’s much harder to do this with the players who maybe are making mistakes or struggling. Who you haven’t connected with. Man, if you start telling yourself that this player fits in this box without doing the work of really learning their story, well, then that’s a problem.

And, so I think the first thing you can do stop building these simple, quick judgements or narratives of kids without doing the work of learning about who they are and what kind of life they’re leading, outside of your team or what kind of things they’re struggling with.

Obviously, the second piece is you don’t have to go above and beyond with this, but you have got to make some time to talk to players. I would argue that particularly road trips are the time to do this. A great time to do this to have those kinds of chats with players and their parents. Are you making some time to have quick chats? To let your players know that you’re available for them if they’re struggling with anything. And you don’t always have to say, “Hey, sit down with me and tell me what’s going on”. It can be more of, “Hey, talk to the group, message us, text us”. Whatever it is, the platform that you’re using, you need to be available for players to openly share with you what they’re struggling with. And you need to sometimes be extra proactive with players, who you know are particularly quiet, or who have a lot on, or who maybe are getting extra pressure somewhere.

Those are the kids you might have to do extra work with who you might want to put some extra time in, in terms of, maybe you need to have that one-on-one. Maybe you need to have a regular call with the folks. Maybe you need to do some films session with them.

I would say that film is also particularly valuable. I know that when we did this particular study, we got as much out of the film study as we did the on-court sessions, particularly when it comes to decision-making. Film doesn’t lie and it’s a bit more black and white in terms of players seeing what they maybe struggled to see while playing, I think when you’re dealing with players who are making mistakes, particularly if they’re repeatedly making the same mistakes. One of the issues that we have is they’ve probably got some bad habits and habits are notoriously difficult for changing just through instruction or even some small-sided games. And I’ve found that the combination of film plus open non-judgemental conversation and non-judgmental is key. Have film sessions. The sessions we did with these groups were often only about 20 minutes and often we would just let you know the group collectively watch what was going on unedited. I know a lot of video tends to be heavily edited, but watch some unedited things, look for patterns collectively so that everybody can land on a small number of things that apply to everyone.

Then, you know, if you’ve got the time, I might do some specific stuff with the individual player, but from a decision-making perspective, what we want to do is make the sort of non-conscious habits visible. This is fundamental to learning. If you want players to make shifts in their style of play, that they own, we need them to become aware of what the changes need to be. So, I think those videos using that film session selectively, but really intentionally, can be very good.

I know our shot selection was the core issue of this team. And we watched a lot of shots being taken. And what we learned very quickly is yep. So, once you start watching shot selection as a group, you see a guy who maybe consistently takes bad contested shots. You also though see that sometimes that’s not his fault. It might be because of spacing is bad and other players aren’t making themselves available.

And that was actually one of the key learnings from this group was that sometimes a bad shot is not always the fault of the player with the ball. It could be the fault of poor spacing by teammates. And then people start to understand, well, he’s not selfish. He’s actually just doesn’t have anybody to pass to because no one’s moved into space.

And I think that those are the kinds of things that can come out of it if you approach it a non-judgmental way where, “Hey, let’s just try to figure this out”. And I think that that’s a both a pedagogical thing in the sense of a coaching tactic, but it’s also a culture, you know, like let’s give everybody the benefit of the doubt that people are trying to do their best and they maybe just don’t realize what they’re doing wrong.

HR: There’s a lot there. Some of the key things I’m taking away, is obviously making the unconscious visible. And something I haven’t thought about too much before, but film being a really good way to do that.

I can also see the value of film being, that there is time between a conflict or issues and then being able to review it.

And then as you said just taking the time to know your athletes. Tactically creating spaces as a coach to do that. As you said, the road trips, away games, those being really good spaces. I’d encourage other coaches to think about what are the other spaces that I can circle off as a space, not just to kind of do sport coaching, but get to know my athletes better. Is there anything else that you want to share or any other key takeaways?

VM: Yeah, I mean, I think kind of a couple of things to kind of finish off. We hear a lot about, you know, coaches encouraging mistakes, learning from failure. We know that growth mindset is all about, this kind of a positioning of mistakes are necessary for growth. what we don’t hear as much about is the actual process of learning from mistakes. And that process is not entirely on the player. It’s also part of the environment that they’re in.

So, we as coaches, we send a lot of signals in how we work through mistakes with players. And so, you know, I think one of the things that I increasingly have done is stopped using even the word mistake as a coach and just think more about a conflict. And learning is about the resolution of conflict. It’s about the elimination of that kind of, you know, issue that’s there until a new one comes, but, but you know, that process of learning from mistakes is a partnership and it’s not entirely on the players to simply stop doing the thing. We as coaches need to give them the freedom to talk about it, to experiment with new ideas, to watch themselves on film, to think about where their conflicts might come from, because I think the players might land on some things that we don’t and that’s crucial because they’re the ones who are playing.

But I think the biggest thing is really that we’re talking about a learning process that’s not straightforward and it’s not going to be resolved simply by just correcting mistakes, certainly punishing players for making them, you know, you know, we haven’t even remotely addressed that side of it, which is usually where coaches start, right?

HR: Super fascinating Vince. We’ll start to wrap up now. If people want to get in contact with you, is there any way they can connect?

VM: Yeah. Happy to respond to anybody who’s interested in this topic or on coaching in general. I can be reached by email, [email protected]. I’m also on Twitter. Happy to get some followers there. And I post a lot of content related to holistic aspects of player development and coaching and sport in society. @PlayerLearning is my handle.

HR: Vince, absolutely fascinating, I know we always enjoy our conversations. One of the take homes for me is, and I know it seems a bit cliche, but just absolutely taking the time, to get to know your athletes. What I’ve really enjoyed with our chat today is how you’ve done a good job of kind of showcasing how you can kind of start from an event or a pattern of events, which this case has been identified as a mistake, but kind of unpacking that further and further.

So, understanding how these young people’s contexts, their worlds, the different things going on might underpin the driver for a mistake or a conflict.

Hey, thanks for joining us today. Look forward to chatting next.

VM: Yeah, this has been awesome.

If there’s one thing to take away, it’s there’s always something happening beneath the surface. And, and just because, you know, a players made a mistake or is struggling, you know, they’re not a bad person. They, they’re not selfish. There are pros to learning that, because you know, we’re coaching young people who are developing. So yeah, thanks for that opportunity to share that. And I hope people enjoyed it.

Read more about Vince’s Research

Negotiating Shot Selection in New Zealand Secondary School Boys’ Basketball: A Case Study

Image Source: Canva