“Make sport fun!”. It seems strikingly obvious. Yet, when you peel back the layers on that word ‘fun’, it gets a little more nuanced. In this article, Athlete Development Project Founder Dr Craig Harrison, recounts his interview with Keven Mealamu, and some of the lessons Keven shared about what made sport fun for him. Craig also delves into some the ‘fun’ research by Dr Amanda Visek.

Growing up in Tokoroa, Keven remembers his childhood as one big adventure. “We used to play down in the creek all the time” Keven recalls when I spoke with him on The Athlete Development Show. “I remember one particular time with my cousins when I got sucked under, and things got pretty hairy there for a moment or two.” It’s something I’d never let my kids do now but at the time it was heaps of fun.”

Keven Mealamu, one of the greatest All Black players of all time, made his international debut in 2002 against Wales at the Millennium Stadium. He had a long and illustrious career, appearing 132 times for his nation and played an integral part of two successful world cup winning campaigns.

Keven describes his childhood as full of action-packed, fun adventures, most of which he shared with his older brother. Just 18 months apart, Keven and Luke were close. They did everything together growing up. When he describes his passion for rugby later in our podcast conversation, Keven recounts falling in love with the game straight away. “I loved the contact and getting the ball and running with it.” He also describes how playing rugby was yet another fun adventure with his big brother.

Mapping Fun – What Young Players Think About Fun

Fun is the main determinant of a young athlete’s commitment and sustained involvement in sport. In 2015, scientist Amanda Visek from the department of exercise and nutrition sciences at George Washington University investigated this idea in a robust yet practical way. Her work led to what is now known as Fun Integration Theory.

In her first study, Visek took a bunch of young female and male soccer players and split them into two groups. The first group included 8-12 year-olds and the second 13-17 year-olds. The kids played at both recreational and the travel team level from a mid-Atlantic metropolitan area within the US. Visek also recruited a group of parents and coaches.

After an introduction to the main objective of the study, she asked the participants to brainstorm a list of ideas using the focus prompt, “One thing that makes playing sports fun for a player is…” Although the participants were recruited through soccer, over 75% of them were currently playing or had played other sports. Next, the participants were asked to sort their ideas into piles and give each pile a name. Finally, using a 1-5 scale, participants had to rate each idea relative to how often it occurred, how important it was to fun and how easily it could be implemented in practice.

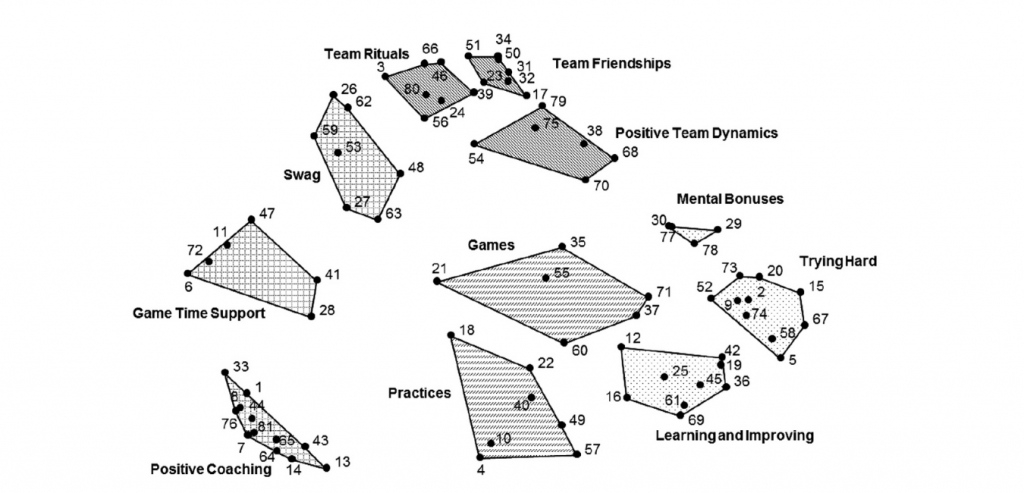

After applying some fancy statistics to analyse the findings, 81 ‘fun determinants’ were identified and represented in a three-dimensional concept map (Figure 1). Inside the map, the fun-determinants were organised based on the strength of their relationship to each other; the closer one determinant is to another on the map, the more similar the two are.

Using further analyses, the following 11 distinct clusters of fun-determinants, which Visek called the ‘fun factors’, were identified: Games, Game Time Support, Learning and Improving, Mental Bonuses, Positive Coaching, Positive Team Dynamics, Practices, Swag, Team Friendships, Team Rituals, and Trying Hard. According to Fun Integration Theory, the way fun is described by players (the fun-determinants), plus how they come together around specific themes (the fun-factors), creates the fun experience.

When the fun-factors were assessed to gauge their relative importance, Trying Hard, Positive Team Dynamics, and Positive Coaching came out on top. Learning and Improving, Games, Practices, Team Friendships, Mental Bonuses and Game Time Support were next, followed by Team Rituals and Sway.

What’s really interesting is that a similar response was seen for girls and boys (~93%), younger and older players (~96%) and recreational and travel players (~94%). This is important because gender, age and level of participation are often cited as differentiating factors when it comes to fun. However, Visek’s research suggests that very little difference exists across various participant demographics when it comes to what makes sport fun.

Fun Can Mean Different Things To Different People

Few would debate that the sporting experience for youth should be fun. The problem is, fun means different things to different people. Mealamu describes his All Blacks journey as taking place in three parts. “At first, it just felt amazing to be there.” Everything was new and exciting and this captivated Keven’s attention. For Keven, fun lay in exploring his new and exciting adventure. But then the real work started. Tomorrow came, and the next day and the novelty worn off. The middle phase of his career was a grind for Keven and it was his love for competition, most likely developed as a kid venturing around Tokoroa with his brother, that kept him engaged. Jostling to keep his starting position forced Keven to be at his best every day and he absolutely loved it. Fun was found in working hard and competing against others. Towards the end of his career, Keven’s motivations changed. Instead of comparing himself to the players around him, he looked inside himself and asked an important question: what would it look like to take my performance to the next level? “Because you’re coming close to the end you want to make sure everything’s done really well. You have much more of an eye for the detail.” As an older and more experienced player, fun for Keven lay in the processes of learning and improving to make himself better.

Visek’s ‘Fun Maps’ describe objectively what athletes perceive to be fun. They provide a useful tool for coaches and administrations to create environments that deliver more positive experiences. However, when trying to create fun experiences, personal beliefs and experiences, or what the current culture of a sporting environment has led us to believe, can get in the way. It’s why using good research to establish the truth is important. In youth sport, despite the player being the primary consumer, she generally holds little control over her experience – the environment in which she plays is typically designed and regulated by adults. So, to deliver the best experience for a young athlete, the personal and emotional biases of the adults involved must be identified and accounted for.

Fun Changes With Age and Stage of Development

In a second study, Visek took the fun-determinants and fun-factors developed earlier and using the same participants compared what the players, parents and coaches perceived to be most important to create fun. The findings showed remarkable agreement between players and parents. Remember that the three most important sources of fun cited by players were Trying Hard, Positive Team Dynamics, and Positive Coaching. The parents Visek interviewed had very similar views, rating Positive Coaching of greatest importance followed by Positive Team Dynamics. This makes sense given that parents act as the most significant socialising agent for a child as they grow and develop. In other words, the perspectives of a child are typically passed down from their parents. What’s more, the importance of the coach in controlling the experience of his or her athletes is a well-entrenched narrative in youth sport.

However, alignment between players, in particular adolescent players, and their coaches was lower. One notable difference between what coaches thought players found most fun and what players thought themselves was how they ranked Team Friendships. Specifically, coaches ranked Team Friendships (i.e., who their players are engaged with on and off the field) higher than Positive Team Dynamics (i.e., what their players are doing on the field). The players ranked the two the other way around. In practice, this may lead to a coaching bias that prioritises opportunities for athletes to be around their friends and to talk with teammates rather than creating experiences that lead to better team dynamics (e.g., playing well together, supporting teammates and showing good sportsmanship). This second study by Visek provides some concrete evidence to explain why sport drop-out rates are higher in early adolescence than in childhood. It also shows why coaches need to talk to their athletes about their experiences.

What This Means For You

Fun is an emotional thing. It’s a personal thing. For Keven Mealamu, the closeness that he felt sharing a new adventure with his big brother made rugby fun starting out. As he got older and his goals changed, fun meant pursuing excellence in his own performance. When asked to recount what makes something fun in our own lives, we tend to describe experiences that are deeply personal, excite and surprise us and ultimately, leave us feeling really good. So, if your job is to create a fun experience for somebody else, keep these important notes in mind:

- Fun is the main determinant of committed and sustained participation in sport

- Childhood experiences set the foundations for what it means to have fun

- Trying hard, positive team dynamics and positive coaching are the top three determinants of fun in youth team sport

- Players and parents closely agree on what makes sport fun

- Disagreement about what make sport fun is more likely between adolescent players and their coaches

- What a player finds fun depends on their age, stage of development and goals they have in mind

Interested in hearing more from Dr. Craig Harrison?

Join his Facebook Group, ‘The Sideline’ – It’s an online community for parents to learn how best to support their child to perform at their best in sport without overtraining, getting injured or burning out.